I had left the Pitusa Hotel early in

November, to reside in Sandy Ground, on the French Side. As described elsewhere

in these memoirs, Yanyi/Yiyi/Xinyi Liu’s mom – my hopeful future mother-in-law,

aka Ah-Ying, aka Sherry Ying – in an effort to help me remain on the island

until, I suppose, circumstances might render me useful, had arranged with a

friend (more like ‘frenemy’) of hers, Amy, for me to live and work in Amy’s

restaurant. Amy – I forget her last name and her restaurant’s business card,

which I still keep, does not have it – had been cheerful and full of promises

to Ying when we’d sat down for drinks and negotiations under the sea-almond

tree in the courtyard of the Honeymoon Spot (long since defunct). She assured

Ying of the grand prospects of her recently-acquired establishment and all the

useful skills I would learn in her service. In private, Amy assured me Ying

would soon come to her senses and realize that, whatever one thought of me

personally, having her daughter married to a dutiful lad with a Canadian

passport was a safer bet for the long term than trusting the whims of a

‘husband’ (boyfriend/sugar daddy), old Reuben Beauperthuy, who was wise in the

ways of the world, and of the ways of women in particular; who was ever on

guard against collectors of auriferous minerals, and whose children and siblings were keen to guard their inheritance from the

painted claws of some Oriental usurper. Time was to prove Amy correct – small

consolation thought it has been.

The weeks of sixteen-hour days

dragged on, my burden lightened only by the fact that the Honeymoon Spot’s

business was mercifully poor, partly owing to its location in a sketchy part of

the French Side far from any of the major tourist or residential districts,

partly (such, at least, was the opinion of Rosie, Amy’s Afro-Cuban aide de camp

– another ‘frenemy’) because Amy insisted that the restaurant’s menu be built

around French cuisine, real French cuisine, with no relation to the islands. Hence,

it had none of the lure of exoticism that drew folks from the tired grey

Metropole to joints with bright, fun, unashamedly Antillean names like ‘Talula

Mangoes,’ ‘the Boo Boo Jam,’ or any of the menagerie of establishments which in

name and/or décor drew on deep-rooted images of Creole belles and West Indian

hospitality. As it was, Amy preserved the cartoonish murals around the compound

which depicted scenes of turn-of-the-last century Sheriffs pursuing rogues on

the US-Mexico border, somehow related to the previous incarnation of the

Honeymoon Spot, with the new addition of French cuisine cooked by Chinese chefs

who didn’t understand it and an Afro-Cuban who disapproved of it, which nobody

was much interested in trying, and which gave bad impressions to those who did.

The only repeat customers were friends and relatives of Amy’s, and Xinyi’s mom,

who once came with Reuben for lunch and had much awkward explaining to do when

Reuben saw that the pesky Canadian troublemaker was still on the island and

had, by obvious inference, been given the means of staying there through the

assistance of Ying herself.

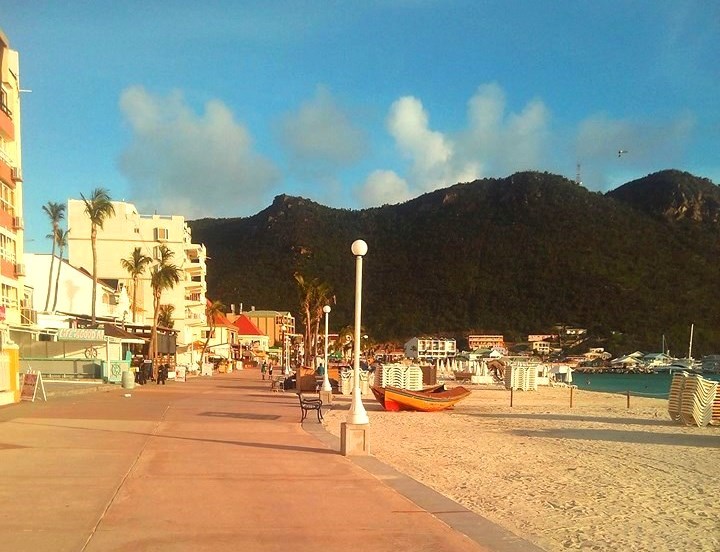

As business failed to pick up and

the chefs she hired kept abandoning ship, Amy grew more lax and I was permitted

to go off on walks into Marigot in the afternoon, where I would feed my soul

with the charming French colonial architecture (in my opinion, the best

colonial architecture by far), the flowers and trees which made the whole town

lush and colourful as a Toronto garden in summer, and the awe-inspiring sight

of the Sea. At that point in my life, I had not yet read Edmund Burke’s essay

on the theory of the Sublime, but I understood intuitively the aesthetic

sensation Burke describes as I strolled below the clifftop fortifications and

stared out at the waves – there, a deep blue-black, not turquoise like the sea

at Philipsburg – the waves and the incomprehensible vastness in which the white

sailing boats tossed disconcertingly, and in which I stood on my tiny, salty

rock.

I wasn’t getting much done, however,

and unpaid servitude in a restaurant, in the most isolated corner of the

island, was obviously not sustainable. Because the Dutch Side was where I’d

first resided and where most of my friends lived, and because, as far as I

could tell, the Chinese community was more numerous and capable of insulating

its affairs on the Dutch than on the French Side (the Dutch SXM police being a

lot more…easy-going…than the paramilitary Gendarmes), it was the natural

assumption that I must seek a job on the Dutch Side. My emphasis on the Chinese

business community was quite logical: who else would hire an illegal? Yes,

maybe one of the strip club brothels (anti-euphemistically referred to as

“whorehouses” on SXM), but the job descriptions…ehh, I likely would not have had

much luck. Thankfully, at the Honeymoon Spot, business was terrible, and, out

of either pity or grudging acceptance that imposing harsher conditions on an

employee who was already working for free might lead to legal troubles, Amy let

me spend weekday afternoons heading over to the Dutch Side in search of paid

employment.

I would take a bus over the

mountains which fill the middle of the Island, disembarking in the lowlands, by

the Great Salt Pond. What to do then? I should add that I did not own a cell

phone at the time. I did the only thing I reasonably could do: I trekked and I

tramped, all along the gravel road shoulder, underneath the scorching tropic

sun, stopping whenever I found a likely-looking establishment and asking the

boss or whichever employees were present if they needed anyone. In other words,

I was doing what the misguided stereotypical Baby Boomer in North American

memes tells the younger generation to do when looking for work (though such a

method has long since become absurd and useless up there). I had only been a

high school student in Canada and had not finished Grade 12, thus it was my

first experience of seriously looking for work anywhere. Naturally, everything

was a rejection, which worried me and made me grow timid. I favoured the smaller

and shabbier establishments (though not so small and shabby they looked like

they didn’t need any staff besides the owner), both grocery stores and

restaurants, both because it was probably that their requirements would be less

(in terms of skills and “papers”) and because the staff were usually more

laid-back and friendly. Mind you, I did go to the gigantic A-Foo Supermarket in

downtown Philipsburg, whose 2nd floor offices resembled a busy

mid-century newsroom or typing pool.

After a day of fruitless searching,

I would stop by at the Pitusa Hotel to pay a call on Wu, the night watchman,

who had become one of my first friends on the Island. Wu lived in apartment in

the rear of the hotel, where it opened onto the back courtyard on the edge of

the Salt Pond. The Pitusa had originally been a grocery store, the New China

Supermarket, circa the 1960s-1970s. Sometime early in the long tourism boom

which enriched the Netherlands Antilles through the 80s and 90s up until the

Great Recession of 08-09, it had been converted into a hotel. In common with

most of the locally-run hotels and guesthouses on Sint Maarten, a fair

proportion of the rooms and suites were not rented out as hotel rooms, but as

apartments on a monthly basis – while I was there, the rates ranged from $400

USD at the squalid bottom to $700-900 or so, with the most desirable apartments

being situated on the second floor, away from the street. In the largest and

furthest-back, with a kind of sunroom overlooking the courtyard lived Teresa Mock,

the owner of the hotel and unofficial empress of the local Chinese community.

The apartments which lined the corridor that ran through the bowels of the

Pitusa from A.T. Illidge Road to the pondside courtyard were inferior in

furnishings and comfort – upper floors, for instance, were created by sliding

sheets of plywood over brackets mounted into the concrete walls. This meant

that the ceiling below was just high enough for a man of average height to

stand up, while he’d have to stoop uncomfortably on the second floor. As a

result of the haphazard partitions necessary due to the converted floor plan,

some of these units were spacious, while some would be condemned in more

well-regulated lands for having insufficient space for their often-numerous

occupants. All suffered from a lack of sunlight and ventilation. The tenants of

these were almost entirely Chinese supermarket and restaurant workers or

migrants from the Dominican Republic, with one St. Lucian family, one set of

Jamaicans and one Guyanese couple rounding out the lot.

Wu and his colleagues – a shifting

set of three to five men who, at least on the Island, lives as bachelors –

dwelt in an apartment that appeared to have been stuck onto the structure of

the hotel as an afterthought, like a barnacle on the body of a whale. It was

cramped, crowded and unbelievably filthy….the seatless toilet was black – not

brown – inside its bowl; the bathing area was a rough concrete trough in which

the occupants (police-phobic Wu excepted) had once slaughtered a kidnapped

goat. A very literally kidnapped goat. I nonetheless enjoyed visiting, because

Wu was a good-hearted fellow and I could watch pirated movies and listen to

Chinese music, of which I was fond. In those days of trekking around looking

for work, he gave me bowls full of oatmeal, cooked very thin and made with

powdered full-cream milk and sugar mixed in, a heavenly refreshment at the

time, as I had no money at all to buy food or beverages (though I could get

water out of the hose round back of the hotel) to sustain me on my wanderings.

I still remember his generosity with extreme gratitude.

One day, where I’d been unsuccessful

as usual, Wu suggested that we go together to a supermarket two buildings down

from the hotel and ask there – he would go as my middleman. Before I proceed

further: the company that operated the supermarket in question is still in

business as of the last time I checked. While the law holds that true

statements cannot count as defamation (put another way, it is a defence to a

charge of defamation to show that a statement is true, among other things), I

nonetheless consider it prudent to change the names of the supermarket and the

owners for the purposes of this account. Besides, several years after I left

the Island for the first time, the supermarket in question moved into new

premises, markedly more modern and hygienic, to all appearances, than the ones

in which I lived and toiled. Too, the hardships now memories, I am immensely

thankful to – I shall him here – Mr. Vong for making available a means by which

I could remain on St. Martin for the sake of my beloved Xinyi, longer than

would otherwise have been possible.

Back in October (it was now very

late in November), Wu had taken me around to “Sunshine Foods” (not its real

name) and asked about finding me work. Back then, though, it was mainly just an

idea to get me more integrated into the community, give me something to do, and

help me pick up the Chinese language – Mandarin being the lingua franca at

Sunshine Foods. I was turned down by Mr. Vong, who (accurately) remarked that I

looked like a scholar, not fitted for the brutal manual labour and long hours

the job would entail. Now, somewhat curiously, although I didn’t look the least

bit more workman-like, Mr. Vong’s attitude was changed. The part of Wu’s

pleadings which seemed to affect him the most was when Wu stressed that my visa

would soon expire, making me an “illegal”…thus, I would not be going to

complain to any labour or employment standards commission. My evident desperation,

demonstrated by the fact I had not abandoned my noble but impractical quest,

also seemed to weigh, although perhaps I am being too harsh on Mr. Vong’s

character.

There were two modes of being a

grunt-level employee at an SXM supermarket back in those days. It probably

hasn’t changed. These were crudely described as “Chinese-style” and “Black-people-style.”

The two methods got the same monthly salary for the same types of work and

levels of experience. The employees on “Black-people-style” worked six days a

week, eight hours a day, got paid fortnightly, looked after their own rent and

food, and went home after work as employees do in most of the Western World.

The employees who worked “Chinese-style” worked thirteen-hour days (with two

hours off in the middle of the day for a siesta, unless it was an especially

busy day), seven days a week (half-days on Sundays), and were paid monthly. The

compensation for this extra labour was that Chinese-style employees got to live

in company-provided housing and got free lunch and supper provided by the

company kitchen. Boss and workers ate together, “from the big pot” 吃大锅饭, as, apparently, is the case in a lot

of old-fashioned Chinese businesses back in the motherland. Since I had no

money for first and last month’s rent on an apartment, and could hardly endure

seven days a week of heavy labour waiting for it while sleeping on the streets,

I opted for “Chinese-style” employment. It would also be better for showing

commitment, for camaraderie and improving my Chinese – which was not a mere

whim, since Xinyi’s mom had truly terrible English.

When Ying found out that I had

secured a position at Sunshine foods, she was delighted…to this day I’m not

entirely sure why. I would remain on the island longer, for sure (and why she

wanted me to do that was not clear either), and I suppose it made up for how

her finding me the place at Amy’s restaurant had turned into such a mess. The

night before I was due to start work at Sunshine Foods, Ying came to up to

Sandy Ground to pick me up in her maroon Suzuki Ignis. I loaded all my worldly

possessions into the jaunty hatchback, then we journeyed back to the Dutch

Side.

The hardships began as soon as we

arrived at the Sunshine Foods workers’ compound, a walled courtyard containing

two low, unpainted concrete shacks. One of these was the residence of the

Chinese “coolies” (the term was still used by the SXM Chinese, so I’ll use it

here). I unloaded my suitcases and stripey plastic bags (what are those

called?), and Ying returned to the Blue Flower restaurant on Bush Road, across

from the Photo Gumbs, where she, Xinyi, Xinyi’s uncle and aunt, and her two

cousins lived.

There wasn’t much to say about the

worker’s dorm. It was a crude rectangle, divided into two rooms by a doorless

portal, each the size of a bedroom in a typical Canadian house. Each room had

cots and the front room had a bunk bed (the top of which I would get, once it

was available), all with rickety red metal frames. Some of the men (not me) had

cabinets for their possessions. Seating was one’s bed or else plastic lawn

chairs and milk crates. There was a CRT TV and a DVD player for the 80s and 90s

films and karaoke tapes the workers sometimes watched (I never saw an actual

television feed on the TV). The bathroom was small, dark, its floor covered in

sand. The shower was a green garden hose with a squeeze nozzle run through a

hole in the wall. I noticed later that a small print of “Chairman Mao goes to

Anyuan” was placed above the interior of the front door, like an icon of a

saint. Fitting for an above of peasant-turned-proletarians. There was no bed

space available to me the first night. A makeshift was improvised. A couple

cartons that had once held jugs of Alberto-brand vegetable oil were flattened

and tossed on the floor. My shoulderbag served as a pillow and a thin cotton

print bedsheet as my blanket. Even under this frail covering, it was like a

sauna. The cinderblock walls – a wretched material for the tropics, popular

because cheap and hurricane resistant – exhaled humidity and there was no fan

(forget about AC) to provide relief. The floor here, too, was dirty and I could

hear the sand scrunching loudly beneath the cardboard as I shifted position.

During the night, I neither slept fully nor quite woke. Extreme fatigue kept me

sedated yet occasionally I would open my eyes (possibly sometimes I was

dreaming), because I was disturbed by the attentions of insects. In darkness,

it seemed (or this was my dream) that I was being ravaged by hordes of ants

that were making a feast of my exposed skin, especially my forearms. I brushed

them off, and scratched and clawed, digging hard under the welts. At other

points, I suspected mosquitos and so cocooned myself in my bedsheet, as I’d

read accounts of US soldiers at Ke Sanh doing to protect against being bitten

by rats. In hindsight, it probably was mosquitos; I had no recollection of

buzzing, but Sint Maarten mosquitos are small and quiet compared to the species

that ravage campers in Canada in the summertime, and I was really half out of

my mind. The next morning, sore and tired, I started work.

I will tell my experiences in

anecdotes; scattered vignettes. That is not unlike how I experienced it.

Indeed, one of the strangest aspects of those days, which I observed and which

struck me as uncanny, even frightening, at the time was how a whole period of

three or four months felt like a disturbingly real dream or a drunken

trance…there was something not quite real about it. Part of this must have been

the simple consequence of chronic exhaustion and the perfectly natural

anxieties caused by being away, thousands of kilometres away, from home and

family for the first time in my life. I suspect, however, that there were

things about the character of where and in what situation I found myself that

affected my mind in ways that would not have occurred had I been equally far or

farther from home, but in a society which operated according to the familiar

and fundamentally homogenous laws of the Metropole; the Big City of the Global

North. The light was different; the angles in which life happened were jagged

and askew – folks in a place like Toronto don’t realize just how flat and

geometrically ordered and uniform their world is, and how disorienting it is to

find yourself in a place that does not conform to such principles. Shocking,

too – first in the “OMG” sense; in the longer term, in the sense that it made

one’s mind operate – was how rules…not the petty superficial ones but the

primal “that’s life”/”that’s how the world works” sort of rules that prevail in

every Big City in the West (irrespective of its paper laws) did not apply.

Nobody was even away of the existence of the worldviews and mindsets which most

everyone take as universal back home. The treatment of animals, notions of time

and space, the isolation or connectedness of the individual; all were

unrecognizable from their Toronto equivalents. On a more formal level, the

understanding that one could not and should not appeal to a higher (temporal)

authority to deal with certain situations, and that one not only can but must

deal with them yourself personally was new. In Toronto, I could only conceive

of calling the police to help Xinyi; people would be angered, critical,

disapproving and mocking (as they were when being told the story later, except

some immigrants and Québécoises, who are less crassly practical) if one acted oneself. On SMX, oneself was the

only way.

With a few exceptions, most of the

staff at Sunshine Foods had no fixed role. So it was for me. Where the boss

thought I was needed (i.e. where my inexperienced labour could be applied most

efficiently), I went, and I toiled, from eight in the morning until a little

after the supermarket closed for night, officially at 9:00 p.m., closet to 9:30

on Fridays and Saturdays. Like jumping into cold water, my experience of the

labouring life in what, really, wealthy tourists, timeshares and resorts aside,

was the Third World, began with a rude surprise, though it did not become more

comfortable with time. My first tasks – to which I was thankfully assigned to

with lower frequency later on – were in the…I shall call it the “packing

department,” as it combined the functions of the produce and meat/deli

departments of a North American supermarket. In one extremely cramped, white-tiled

room, divided for half its width by a partition wall, vegetables and fruits

were shrink-wrapped into Styrofoam trays, bulk foods like brown sugar (GUYSUCO)

were taken from hundred-pound sacks, weighed out into plastic retail bags and

bar-coded.

In this same room, a few feet away, wholesale

cases of imported frozen meat were dumped out onto a long stainless steel

table. Workers, armed with metal scoops, would stab at the heaps of

fast-thawing flesh and shove the bits into bags, which they would weigh on

digital scaled and printout barcode stickers for (five pounds people a common

size, though this varied). I say “stab,” because one of the worst features of

the work was the savage pace. One had to dump, measure and pack hundreds of

pounds of meat at a speed that required punching with the scoop, twirling that

bag and smacking on the barcode sticker as faster than your limbs could sanely

move, hampered as they were by the slimy texture of the objects one was packing

and the slipperiness of blood and grease-smeared hands – no gloves, and, of

course, one always had to snatch up some errant fragments with one’s fingers. I

mention “fast-thawing” because any frozen item would thaw quickly in that

stifling heat. There was a fan mounted behind a grate high up in the wall, but

it accomplished very little.

In the same room, ground beef – of rich ruby

colour and unnervingly high fat content – was produced by dumping

couple-inch-square blocks of meat from cases marked “stewing beef” into a

sturdy, Age of Steam-looking Hobart grinder. There was also a meat saw, whose

exposed blade, in those cramped, slippery, rushed conditions, cost one St.

Lucian and one Haitian meatcutter most of one hand each within the brief span

of about six months. The saw was used to chop down beef shanks, oxtails, ribs

and frozen beef tripe into chunks suitable for retail. The ground beef shanks,

tripe, oxtail etc. were scooped and packed the same as turkey wings, chicken

feet and the like. Chicken feet, pig snouts and pig ears were packed into Styrofoam

trays. I remember the oxtail as having an especially nasty texture in the hand

or crushed against the lip of the scoops. The barcoded bags or Styrofoam trays

were piled into spare shopping cards, then wheeled out for shelf-stacking by

either us packers or other employees. The vegetable and fruit section was

obviously preferable to work in compared to the meat section, though we did

sometimes have to pack, using the same equipment, gross things like salted pig

ears, pig tail and pig snouts, all of which came off a ship in plastic tubs

from Drummond Export, of Drummondville Québec – these and the buckets of pork

lard were all emblazoned with the logo of the company, which was a maple leaf

and a crude map of Canada. Every day, I saw the image of my country, which felt

a little weird, given the strange products it was attached to.

The meat section was exponentially

more busy than the produce section, because both Saint Martiners and

Dominicanos (the largest ethnic minority and a huge block of Sunshine Food’s

customers), in general, do not have so much of a fondness for vegetables and

fruits, both cuisines being extremely heavy on the meats and dry and fried

starches. Hence, a supermarket, catering to such a clientele, could hardly

resemble, say, an Asian or Middle Eastern supermarket in Toronto or Vancouver,

with lavish and colourful mounds and pyramids of the fruits of “every

herb-yielding seed.” Worst of all was clean-up duty in the meat room, a

grotesque misery to put a spoiling touch on the end of an already long and hard

day. It meant being stuck alone with the St. Lucian meatcutter, an insufferable

prick who took a Calvinist’s delight in his toil and made a point of being a

thorn in my side. The general attitude among all the workers was akin to that

of prisoners in a gulag – in a positive way, i.e. we all have to serve out our

time together; let’s try not to make it any more unpleasant than it has to be.

The Lucian meatcutter, whose name was Cyprian, had a Gossip Girl enthusiasm for

bitching, in whiny, snivelling fashion, to the boss about this or that issue,

including his coworkers, of which I was just the worst; the veritable bane of

his existence. He was short, wiry (though he rapidly fattened when no longer

employable), with a bouncy, childish exaggeration to all his movements and

sentences. In contrast to his habit of effeminate whinging, Cyprian was ever

boasting of his sexual prowess, as if the whole world’s women must wish for

nothing more than a 5’5” St. Lucian meatcutter who smells like a rotting

carcass. He seemed to have a particularly strong dislike for white people and

Chinese (not too keen on Jamaicans, either), and tried to inflame my temper

(not without some success) by making insinuations about Xinyi, which neither

evidence nor rumour corroborated. Judging from the occasional fights with

Chinese workers, I assume he was no comrade to them either.

At

the end of the day, the room would be strewn with fragments of bone and

gristle, some of it in the form of “meat sawdust” generated by the ever-busy

saw, and some undoubtedly hidden or overlooked relics of the previous day’s

work. The stink was terrible; imagine being locked in a small room, in 30-plus

degree heat, with roadkill that’s just starting to ripen. The process of

cleaning involved hosing the whole room down – bits of meat would ricochet and

gum onto one’s face or clothing – while dousing all surfaces with bleach. The

bleach water would be wiped on tables with rags and pushed as a floodtide along

the floor with a broom, dragging animal detritus with it towards the floor

drains. This carcass-water would be a centimetre of two deep, and would absorb

into the foam and fabric of one’s shoes, making them reek incurably. I threw

out the pair I’d worn there immediately when I quite the job.

I was a vegetarian before I went to

SXM, but I gained a powerful new reason to remain one during my time there.

Stocking shelves at Sunshine Foods

was the same as one might know from a North American grocery store, though,

because of the old fashioned technology, most every item had to be slapped with

a paper sticker listing the price in Netherlands Antilles Guilders. I liked stocking

shelves, compared to some other tasks, although I was not very good at it

because I worked slowly (sometimes out of a subconscious desire to avoid

something worse), and, due to my inexperience, I always had to go running to

Hardat Singh, the Indo-Guyanese chief stocking person to ask what price to

stick on which product. A good chap. The best parts of shelf-stocking were that

it was lighter than some of the other jobs, I wasn’t being watched by an angry

manager all the time, and, most of all, I got to interact with members of the

public, who were often quite forward in striking up a conversation with this

curiosity that I was – a white boy, with manners that indicated a bourgeois

upbringing, doing menial and probably under-the-table labour in a Third World

country. Usually, people assumed I was Dutch, or a pale Latin American. One old

Rastafarian, with a sharp eye and well-travelled mind, greeted me and told me

he knew I was “Russian.” Close enough. He never asked me why on earth I was

working there – something everyone else did, if they spoke to me (or they might

speculate on it with a shopping companion). He merely smiled, mentioned

cryptically that he had been to many places and seen many things, then stated,

more in the manner of a theory than a friendly complement, that I was “a good

person,” and left to finish his shopping. Unusual, so it sticks in the memory.

I also met the first illiterate

adult I’d ever encountered, a middle-aged man who asked me, in hushed tones, in

regards to a can he was holding, if “this says Jamaican cheese on it?” He was

not blind, and scrutinized the tin of cheese as any consumer might when they

were reading ingredient labels and so on. The tin was one of those big red

cylindrical tins which are still used to package the Jamaican version of

cheddar cheese, which, as far as I can tell (living in Kingston now for nearly

three years) is the only kind of cheese produced here. It did in fact say

“Jamaican cheese,” in big, bold block letters on the bright red-and-yellow tin.

Sad; an eye-opening lesson that not all of the world has had the advantage of a

basic education, something taken for granted in Canada, and of the painful

embarrassment the illiterate must feel on the fringes of the 21st

century world.

Two added bonuses to shelf-stocking

were Eurodance music and a chance to see Yanyi or family members of hers that

came in for shopping. I love 90s Eurodance, though I was much too young for

clubbing when it was being made. Ah, Z103.5, DJ Danny D (!!!), live-to-air

Wayback Wednesdays at Club Menage…Unfortunately, Eurodance is not popular in

the Caribbean. On Sint Maarten, one heard it but rarely, most often blasting

out of a passing Frenchman’s car. Rarer still, a song would be played over the

radio while I was out stacking shelves – the sound was best by the dairy case.

I remembered one particularly good song (much of the impression no doubt being

from the comforting taste of the fondly familiar), which took me years to find.

Googling was no help. A chance clock on a YouTube sidebar some nine years later

and I learned it was “Self Control” by Cardenia. There was, more frequently, a

lot of 80s pop-rock, which I don’t mind, but don’t love, either.

A couple weeks after I started work,

I was told by more than one colleague that Xinyi had been in the store. She’d

come with her uncle and cousin to grab a few things for the restaurant. The

rumour was credible, since all the Chinese staff knew Xinyi Liu by sight – she

came in all the time when her family lived at the Pitusa – and, if they wanted

to BS me, they could have driven me mad with reports of more sightings, but

they did not. Sadly, I was either in the back or, more likely, on delivery

then, and missed her.

Another duty which views with the

meat packing room for awfulness was garbage duty – heaving the damp garbage in

my arms into the truck, jumping around in the bed and beating the accumulated

filth with a metal pipe to compact it, and the trip to the dump itself. But, I

have written of that specific part of my experiences on SXM elsewhere, so I

will not bother with it here.

The manner in which the garbage was

handled was only one of many unscrupulous practices the supermarket engaged in.

It is very easy to understand, for me, why whistle blowers in the case of X

corporation doing illegal and hazardous whatever, are so rare and why, when one

does come forward, it’s usually some disaffected officer or higher-up. In any

situation where the worker has a rich and benevolent State to cushion their

fall, the power differential is inevitably moderated; X corporation can

threaten disloyal servants with demotion and the loss of their bonuses and

privileges, but they cannot threaten true destitution, homelessness and

starvation because they do not have the means to deprive anyone to quite that

extent. When one is looking down the barrel at such Fates, however, and where

there is no immediate harm to anyone, there is little motivation to turn

whistle blower and dedicate one’s time and energy (a mere shadow of which

remains at the end of 80-hour work weeks) to becoming a noble public servant,

particularly when you know that society as a whole and, especially the State,

does not give a crap about you. On the other hand, I was quick to warn my

friends and acquaintances about the sharp practices that we employees were

compelled by the need for food and roofs over our heads to facilitate. Personal

connection and knowing somebody won’t rat you out for the heck of it makes a

big difference.

Probably the most legitimately

dangerous practice, one with an actual potential for causing harm to a

customer, was that of mixing old meat with new. I have mentioned the meat packing

tables and the practice of scooping chunks of the relevant carcass part into

clear plastic bags of several pounds’ weight, making a barcode sticker for each

bag and placing them out for retail sale. While business was brisk, it was

possible that some bags did not sell. The problem for a specific bag would grow

exponentially more acute as discerning customers noticed the increasingly

spongy texture to their squeezing, prodding fingers, the soggy label that

showed a relatively distant “packaged on” date, and the off huge of the bag’s

contents compared against its neighbours. The fresher and staler meats had to

be the same price. Even in a relatively underdeveloped country, it would be a

source of scandal if it were known that locals had to buy rotting meat at

reduced prices while tourists and expats, who generally have more money, got

fresh goods at the Grand Marché. Also, even if there was no violation of the

letter of the law by this sort of meat-selling tactic, the hipster fad for

extreme-aged meat had not caught on in Soualiga. A means of disguising the old

meat had to be found. The solution adopted can hardly be called ingenious, but

it was effective.

The bags of meat in the display bin

which were adjudged unsaleable were taken into the packing room, slit open and

spilled out onto the packing table, one or two at a time. The bags plus the

attacked – and dated – barcode labels were discarded. It is important to point

out that this process could not be done at just any time. It had to be saved

for when more of the same meat product had been taken from the freezer

container in its wholesale cases to be laid out onto the packing table and

bagged for retail. Once there was a big heap of turkey wings, stew-beef cubes

or oxtail segments on the table – fresh ones – the meat from the unsaleable

bags would be vigorously tossed in and blended with the heap, mixing old and

new thoroughly enough that, chunks jammed together in a clean, taught new bag,

supported by a freshly printed barcode label with a new packing date, the

consumer would not notice…hopefully. It is important to add that, to the best

of my knowledge, nobody became ill as a result of any of these practices. The

unsold meat mixed and repacked was never rotten completely, though I do recall

it being strongly discoloured (oxtail and stew-beef darkening especially much,

with a noticeable green hue) and changed in texture – if it weren’t altered in

quality to the point it would repulse a customer, there would have been no need

to waste precious work time on the above-mentioned procedures. Once or twice, a

savvy Soualigan, who no doubt had heard rumours of the nefarious tricks

employed by Chinese supermarkets, would call my attention to the questionable

appearance of the meat on display, challenging me about the honesty of our

labels and the source of the products. Such an individual usually gave a brief

tirade about the dishonesty of certain grocers, the superior ethics of other

eras, ethnicities or establishments, and then left without purchasing anything.

The majority, evidently, were perfectly satisfied with our goods.

Fruits and vegetables did not escape

the schemes of the unscrupulous managers. To this day, I am sceptical of

shrinkwrapped Styrofoam trays that hold their contents too tightly. I have

reason to be sceptical, since I practiced all these techniques myself. Now, to

a certain extent, the shape, size and susceptibility to bruising of different

varieties of produce govern the choice of packaging. Fair enough. Nonetheless,

I would advise the reader to be wary of any supermarket that makes a

disproportionate use of those tray packs. The choice to use them is often

deliberate, for the worst of reasons. A veteran worker showed me a simple trick

that provoked an “oh, that’s why they use these” from me. Tomatoes, especially,

though also apples and plums, tend to develop mould and bruising in localized

spots. If these fruits are stacked in a pyramid, like in one of those colourful

photospreads of an Afghan market in a National Geographic, it is easy for the

customers to detect. Moreover, on discovery that they’ve been handling rotting

or mouldy fruit 0 perhaps having even got some of the spores and juices on

their fingertips – the customer will be disgusted and will be less inclined to

buy any of the fruit in the display, even the perfectly sound ones. But…if you

place the fruits on a Styrofoam tray, mould spot or bruise-down, then, making

sure not to disturb the fruits as you do it, shrinkwrap them tightly so that

the mould or bruises are pressed firmly into the bottom of the tray. No matter

how the customer tilts or shakes the tray, they will not be able to discover

the flaws – not till they have taken it home and opened it up to eat.

The cabbages and lettuce sold by

Sunshine Foods might have appeared peculiarly small compared to those sold by

places like the Grand Marché (the standard of quality food on SXM). This had

nothing to do with the variety or source of the vegetables – they were generic

types sourced mostly from California via Miami, like anywhere else. Lettuces

and, even more so, cabbage, tend to yellow and rot from the outside in. Thus,

when the appearance of a head of either fell too far below the level at which a

customer might buy it, it was taken in back, near the shipping containers used

for storage and the refuse heap. We would squat on milk crates atop the damp,

uneven concrete floor, lay down an empty cabbage box in front of us, and go to

work on the refuse heads with a heavy-bladed knife, hacking and peeling the

rotten leaves, the box conveniently collecting the waste. The “fresh” head,

paler and much-reduced in size, would of course be re-bagged with labels

declaring the new packing date.

Canned goods were safe from us, but

if a frozen or dry item was in a plastic pack with a best-before date inked on

at the factory, should such a date be passed, this could also be dealt with in

the packing room. Nail polish remover will take off the best-before date

without producing any blurring or discolouration of the packaging. There’s no

indication that there ever was a best-before date. I remember we had to do this

once with a huge shipment of harina Pan – the white cornmeal that is used to

make the staple arepas, pupusas etc. of Venezuela and Colombia. Incidentally,

harina PAN is the best-tasting cornmeal in the world, and I have eaten cornmeal

from eight or nine countries. I think it was still exported from Venezuela back

then. Grotesque economic mismanagement and the neglect of agriculture by the

Chavez-Maduro government has since put an end to that.

That one Lucian meatcutter aside, I

didn’t have a particularly bad relationship with any of my coworkers. There was

one Jamaican forklift driver, a friendless workaholic whose rigid and demanding

attitude and obsession with extreme rushing in all things did not endear him to

his countrymen, let alone the rest of us. Thankfully, I saw little of hi, since

he mainly worked at the mat warehouse in Pointe Blanche and, for probably

coincidental reasons, I was not sent there much. While we didn’t all like each

other, and there were a couple rivalries, such as between the Dominican and

Haitian delivery truck drivers, who hated each other for the reasons Dominicans

and Haitians hate each other, there was sense of being in the same boat. While

we might not enjoy it, we were all sailing together and each had to do his lot

to make the journey less miserable for all. Those few, like the Jamaican

forklift driver and the Lucian meatcutter, who bought into the creed of “work

shall set you free”…neither of them gained very much for their gleeful

embracing of their penance.

I did have to go, very regularly, to

the Cole Bay warehouse, which was the dry goods warehouse for things brought in

from the shipping containers in the Port, but not yet needed on the retail

shelves. Here we stored all the uber-popular items like NIDO milk powder,

pasta, vegetable oil, various kinds of kecap

(the sweet Indonesian soy sauce necessary for Nasi Goreng, a fast-food staple

on the Island thanks to the Dutch Empire’s broad reach), dried beans, hot

sauce, Busta soft drinks and soy milk, which is very popular and cheap on Sint

Maarten. I almost forgot to mention ROMA detergent powder. The coarse, crumbly

blue-flecked white powder with the dutiful, over-dressed Latin American

housewife on the label was by far the number one choice across the Island for

cleaning clothes and, allegedly, dishes as well. All these items were in

wholesale packages, which presented some difficulties because of how we had to

handle stuff. The ceiling of the warehouse was very high, taller than the

average two storey house, and the shelves went almost right to the ceiling.

There were no ladders or stairs. Reaching the top was effected by riding on top

of a pallet, lifted by a forklift, up to a certain level. One person would be

packing the pallet. Another person got onto the shelving structure and climbing

up the even higher level where the goods in question were stored. These would

be handed or tossed down to the guy on the pallet being held up by the

forklift. There were no Health & Safety inspectors, so who was to say it

was an improper method of work? I will say that walking around at that height,

on a wobbly shelf, with a hard concrete floor below, with the tops of cans,

bottles and boxes as your (very unstable) floor, is nerve-wracking by itself.

It was a good deal more nerve-wracking straining to prise out the appropriate

number of thirty or forty-pound cases of whatever product and move with them

safely, always being yelled at to speed up and knowing that, if you moved too

slow, you might be out of food and shelter when you arrived back at the

supermarket. It wasn’t any better for the guy on the pallet, who had to somehow

pack it securely, making sure not to drop anything (a wholesale case of tomato

paste or a forty-pound box of detergent dropped from twenty-odd feet would make

a bad day for whoever it hits), while the platform on which he is standing gets

continually smaller and more uneven.

Liquor and beer also came to the

Cole Bay warehouse in shipping containers on the backs of trucks, but it was

not left there. It was tossed down, by the case, from the containers, to

workers below, who packed it onto pallets, which were loaded by forklift onto

trucks for delivery to a locked, gated-off section inside the warehouse area of

the supermarket itself. It always worried me when we had to unload a container

of booze, especially Guinness. The tall bottles, made of thin glass, broke

easily. This was a problem for us workers because, if a case broke, it was

supposed to come out of our paycheques at the end of the month. $40 or $80 is a

lot of money to have deducted when your monthly salary is $400 to $900. Sweaty

hands from the intense heat, the height from which the cases were tossed down

to forearms which became pretty bruised up (sharp sided cases of beer flying

into your arms a couple hundred times in succession will do that), plus the

attitude of the owner’s brother, who supervised the Cole Bay warehouse, ensured

dropped cases were a regular occurrence. “John” Vong spoke quickly and with a

stutter, and what he seemed to think words meant did not necessarily match what

they meant to the person he was yelling at. Every day, all the time, it was the

same…I can still hear it in my head, his familiar catchphrases. “You wuh-king

too slow! Fast-fast!” “You packing no good! You packing no good!” I never

witnessed any speed of work satisfy John’s wishes. As for how one was supposed

to arrange the layers of items packed on a cargo pallet…admittedly I was a

complete rookie, but, you try packing a pallet that must be stacked to the

height of a man or higher, with bones, crates, tins, bottles of entirely

different shapes and sizes. Once or twice, Mr. “You packing no good” got egg on

his face when, after reprimanding us coolies and showing us how it was done,

one of his self-packed pallets collapsed and made a mess. Curiously, this never

provoked any change of mind on his part. He would just look at us and grin and

laugh stupidly, his face looking for all the world like an Asian version of

former president George W. Bush.

We “Chinese-style” workers, of which

I was the singular non-Chinese example, really did “eat from the big pot,” so

to speak, boss and workers at one table, in a kitchen at the back of the

supermarket, dark and dingy as a coal mine. The usual chef was Ah Long, or

Zhang Long, a lively, cheerful young peasant from Zhumadian in the central

Chinese province of Henan. He was also the baker at Sunshine foods, who every

day except Sunday made the five-for-one-US dollar “titi” bread that was

Sunshine food’s most famous specialty. Titi bread itself, as far as I have been

able to discover, is a specialty of St. Martin and possibly a few neighbouring

islands in the Lesser Antilles as well. Ah Long was a good cook, and Henanese

food is hearty, warm-flavoured food very suitable for labourers exhausted at

the end of a long day. It made sense, as most of the coolie workers were

Henanese – the boss’ family were from Jiangxi and two of the foreman-level

workers were Cantonese. Even the harsh and not very culturally-sensitive bosses

on the transcontinental railroads, during their construction, found that, while

the Chinese would work hard and long for little pay, they could not be without

at least a basic semblance of their accustomed diets. The major change which

the workers had to endure was in eating rice every day, something they’d never

done before moving to the West. Ironic, given how, in North America, it is

believed that all Chinese eat rice as their sole staple. However, the heartland

of China does not grow rice in any great quantities; my fellow coolies, all

peasants in their homeland, grew wheat, corn and sweet potatoes – never rice.

It also helped that Henanese cuisine, with its emphasis on strong flavours and

techniques like braising and stewing, is not so critical of the freshness and

quality of ingredients as the lighter techniques and tastes of, say, Cantonese

or Fujianese cooking. You see, the food for us workers, for economy reasons,

came off the shelves. The cabbages and lettuces which could no longer be

chopped down and re-packed; the apples too bruised for the shrinkwrapped tray

trick to work anymore…A too-common dish was a watery soup, the bulk of which

was provided by a sack or two of golden apples – I’m not sure of the cultivar

name – chopped into large pieces and boiled.

As far as I can tell, this had nothing to do with any culinary culture;

nobody would buy the apples and feeding them to us, who had no choice in the

matter, saved using something else that the penny-pinching managers would have

to fret over. The apples had their sweetness neutralized in the huge soup pot

and they didn’t have a very appealing texture. Potatoes would be the logical

choice, to most people’s tastes, but potatoes store well and are in high demand

on SXM, hence I don’t recall a single occasion where we had potatoes in the

soup. To this day I’ve not eaten another golden apple – and definitely not as

soup. At least we didn’t develop scurvy. In terms of quantity and quality, the

food was adequate for Third World coolies who hadn’t the cash to supply their

own.

All the workers lived with were either Henanese or

Manchurians. The Manchurians were swaggering and prideful, fun to hang around

with and fond of drink – the Russians of China, if you will. One particularly

spritied fellow, who went by “Mark” (real name Ma something or other), was an

actual Manchu who looked like this watercolour portrait of one of Qianlong’s

Imperial Guard that’s often reproduced in history books. He was a fanatic

Manchu nationalist who believed that Manchuria should be independent of Han

rule and that the Qing Dynasty should be restored. Mao became a minor legend,

the fame of which even extending to some of the black and Dominican youth in

the neighbourhood, because of an incident at the potato containers. Sunshine

foods had a couple ‘reefer’ containers parked on an empty plot of land, not far

from the supermarket, which were used for storing potatoes. Almost all the

potatoes one ever saw on Saint Martin (Dutch Side or French) were the same

type, which I figure must have become dominant due to some

colonial-guilt-ridden subsidy agreement. They were lumpy and covered in

blackish clay, packaged in fifty-pound burlap sacks labelled “Dutch Table

Potatoes” and, unsurprisingly, were produced in the Netherlands. The boss’

brother was supervising a gang moving a quantity of potatoes, and he must have

gotten a bit too zealous in ordering and insulting the workers. The Manchu, in

a shocking display of insolence (or a righteous defence of his proper dignity

as a descendant of the great Qing), fought back – and not with words alone.

From a position atop a mini mountain of potatoes, he hurled lumpy, muddy tubers

down upon the boss’ brother, hitting him numerous times. Shockingly, he was not

fired, and afterwards boasted with justified pride of the occasion.

The Henanese were solid peasant

folk; the archetypal humble tillers of the soil, tolerant bearers of burdensome

Fate, possessed of preternatural patience and endurance that was romanticized

in Hollywood and Western literature about China for so long, but which is so

rarely met with among the Cantonese who form the bulk of Western Chinese

immigrant populations. Taller than their Southern compatriots, with distinct

longish rectangular faces, calm teardrop-shaped eyes and frequently with wavy

or curly hair, they are generous folk, in my experience. Poor as they

themselves were, my coworkers often helped me with small gestures of kindness.

Seeing me walking in my socks on the sandy, grimy floor of the dorm, they

bought me a pair of sandals. Seeing that I was trying to learn Chinese, I was

given a couple little books to assist. If I tried to pay, my money would be

refused. On the other hand, they were generally terrible businesspeople. While

it was a common path to leave Sunshine Foods and set up a restaurant as soon as

one had saved up enough (not too long, in spite of the low salaries, due to the

extremely low threshold costs for starting a business on Sint Maarten), the

restaurants established by Henanese were typically smaller, less fancy and less

successful than those of their Cantonese counterparts and none of the truly

fashionable, big-name Chinese restaurants (or supermarkets) were owned by

anyone but Cantonese. Because of the background of my colleagues, and because

this was in the days before everyone was on social media, I have long since

lost contact with all of them.

By far the best task to be assigned

to during my days at Sunshine Foods was assistant to the delivery drivers who,

God bless them, kenned my state of mind and took a shine to me, and make it

clear to the boss that they liked having me as their side man on delivery

trips. The bosses, for their part, liked to have me out with the delivery

drivers because they suspected the drivers of using company time and gas for

private purposes and occasionally taking an extra case of this or that common

good from the warehouse to sell on their own account. Both suspicions were

well-founded, as I personally witnessed. An extra case of Baron hot sauce sold

to the Dominican shop beside the brothel at the Dump (my silence purchased with

a very tasty Dominican rice pudding); a 24-pack of one-pound sugar bags stashed

in the driver’s private car for him to sell later; an hour spent waiting in the

truck, parked near the airport on the French Side staring at the bucolic

scenery as a driver visited one of his women and came back with some jugs of

local moonshine.

I am proud to say I never ratted, and if an

employer thinks that is unethical, then so is feeding people greening meat and

paying for heavy manual labour at a rate of $1.13 US an hour (extrapolated from

my monthly salary). I should add, this was in a country where the minimum

monthly wage was $600-800 USD, calculated on forty-hour workweeks. In my first

month, despite a promise of minimum wage, I got $400. As I recall, it was $450

or $500 the next month. The Haitian (“Pappy”) and Dominican (who was called

something that sounded like “Hadda,” but I never saw it spelled on paper) might

have hated each other, but they were kind to me, rescuing me, albeit

temporarily, from the nasty, brutish labour and bullying and insults associated

with the other tasks I might have been put t. It was also an incredibly

enriching experience.

In the mornings, we’d get a list of

the places we’d have to deliver to and what their order was. I’d grab a titi

bun or two and a bottle of water and we’d hit the road. There would be

restaurants, bars and supermarkets, French Side and Dutch. The supermarkets

were mostly small ones – sometimes nothing more than a zinc-roofed shack – that

did not have their own warehouses or sufficient capital to order whole

containers of goods directly from Miami. Sometimes, though, we would deliver to

a huge supermarket, such as Sang’s, which was vastly bigger and more modern

than Sunshine Foods. Presumably, this would be because they happened to have

run out of some specific item which we still had in stock and the owner, being

Chinese, preferred to deal with another Chinese (the Grand Marché never ordered

anything from us, as far as I can remember). Some of these establishments were

owned by blacks of different nationalities – the Haitian driver, Pappy, forced

me to show off my French, talking to some shopkeepers he was friends with…other

Haitians. He took great delight in this, as did his friends. They saw

themselves as members of Francophone culture, in a way, and regarded the

language as infinitely superior to English. A couple were owned by Indians. I

remember one bright but tiny and cluttered shop run by a Sikh, one of the only

ones I ever saw on SXM, in a location very out of the way, where the trees

seeped like veins among the scraps of civilization, and the angles of the roads

and buildings were disorienting in the extreme. A lot of places we went were

like that, had that effect on me, especially in the mountainous middle of the

Island. The whole experience felt like a drunken dream, although I didn’t drink

and my actual dreams in that time were few and unremarkable. It was some queer effect

of the lighting, the atmosphere, the extreme and irregular geometry. That and

the emotional state I was in, finding myself in a totally new place – a new kind of place – for the first time in my

life, and experiencing that while I was facing the problems of poverty and

being an illegal alien, etc. I should add, there was another benefit of

delivery work related to that last point: I escaped the immigration raids that

were sweeping the Dutch Side at the time. Once, me, Pappy and Wang Hemin (one

of my dorm mates) were pulling out of the Sunshine Foods parking lot, nosing

our way through the chaotic traffic just as the VKS and Immigration police were

finding their own parking spaces. They carried off a couple people at Sunshine

foods that day. I suspect, though, if I were to return to those parts today, I

would feel them equally different to the Metropolis as they felt then, though

my sense of their difference would be more curious and approving than confused

and fearful.

By far the majority of our customers

were Chinese, and here both my rapidly growing knowledge of Mandarin and my

personal identity came in handy. History and stereotypes led to me frequently

being taken for a manager/boss by the clients, who would approach me as the man

to deal with, which felt nice. Most important of all (to me) some of these

grocers and restaurateurs knew Xinyi and her family, and so were valuable

sources of information and encouragement. I was also introduced to an aspect of

island life that is absolutely hated by a lot of people – I myself relish it.

This is the fact that, especially if you for whatever reason especially stand

out (I did), everyone will know what you are up to. Go to town to a restaurant

and an internet café? The people back at the hotel probably know what you were

up to before you reach back in the evening. I remember the first such shock

very well. We were delivering with the Nissan pickup, to the Hong Kong

Restaurant and Supermarket at Cornelius M. Vlaun and Cannegieter Streets. I had

never eaten or shopped there, and had never seen any of its employees in my

life. Some of the Hong Kong’s workers had come out to help us move the stuff

off the back of the truck more quickly. I noticed that one of the men, black

shirt, somewhat spiky medium-length hair, was looking at me rather intensely.

“Hey, you’re the guy who’s come from Canada to marry…” he either said “to marry

Ah Ying’s daughter,” or “to marry the woman who owns the Blue Flower’s

daughter,” which amounts to the same thing. Speaking to me, but for the other

parties gathered round, he gave a brief synopsis of my purpose in coming to the

Island and the difficulties I’d encountered up to that point. While I’ve since

come to accept such a thing as part for the course of Antillean life, in my

whole lifetime I’d never had an encounter like that, and I reckon the natural

reaction of the Toronto mind, running into some never-before-seen random fellow

who knew where they were from, where they resided and who their significant

other was, would be to call the police and report a case of stalking. Once I

got over my initial surprise, it was flattering that the story of Mike and

Xinyi had already spread far and wise, and was considered exciting enough to

gossip and inquire about.

The Peking Supermarket was another

of my favourite places to visit on delivery. The woman who was usually the

cashier was an attractive, sweet-natured thirty-something who knew Xinyi and

her mom from playing mahjong together and other social activities. She and her

colleagues were cheerleaders for my quest; the boss lady and her friends

giggled with glee at my demonstrations of speaking Mandarin and writing Chinese

and were of the opinion that me and Xinyi getting together would be a very good

thing for all concerned – enough to put someone in my good books. Her name

slips my mind, but I remember fondly all the people who could see something

sweet and valuable in our romance. I noticed that it was a rule, with almost

the sureness of a mathematical law, that the uglier and more miserable a woman

was, the more hostile, mocking and disapproving she would be of me flying down

and undergoing all of the adventures I was undergoing to be with and help

Xinyi, whereas, beautiful and happy women would invariably feel that it was a

sweet and touching story and would wish me and Xinyi success and happiness

together.

The boss of Sunshine Foods was a

tall, slim, dapper gentleman with an anachronistic moustache. He asked me often

about things, and even made me tell the story at the ‘big pot’ dinner table.

His wife, an ungainly, shrill-voiced woman with a face for which “a bleached

frog” is the most apt metaphor, on hearing the story, became pointlessly

indignant. She huffed and puffed furiously and outright declared that she

refused to believe it; refused to believe that a young man from a good

middle-class family in Canada (which she had visited but was herself unable to

immigrate to), would leave everything to fly down here for something so silly

as love – and for a girl whose family had nothing to offer in the way of money

or prestige, and were, to put it lightly, known as not the nicest people to

deal with. “I don’t believe it! I’ll never believe it!” she shouted over and

over. Aye, that I would leave Canada

to become, voluntarily, an illegal immigrant and endure such real hardships

as…working for her and her husband! I asked, rhetorically, why else would I be

down here, doing this? She well knew it couldn’t have been for the money!

Yes, the pay, for all I put in, was

not much, but, because I was working “Chinese-style” it was all mine – no need

to spend any money on rent or food (for the most part). I used my first month’s

pay to buy a cell phone, one of those indestructible blue-and-white Nokia stick

phones which had long since been phased out in Canada but which were still

popular on SXM. This would allow surreptitious communication with Xinyi, which,

up till then, had to be done by email when I went into Philipsburg to visit the

internet café (Cyberlink, was it?) in a mall that backed onto the Pondfill…can’t

remember the name of it. Was it the Percy M. Labega Centre? At the time, Xinyi

and I didn’t talk much on the phone – there was still a lot of awkwardness and

the rageful hostility of her nominal stepdad, Reuben…the whole situation I

would not understand for a couple months yet.

The brutal work schedule put an end

to the weekendly group trips up to the Boo Boo Jam in Orient Bay with Keon

Scott, Guyanese Ricky and whoever else was tagging along. Notwithstanding that

inconvenience, my schedule at least allowed me Sunday afternoon off, after 1:00

or 2:00 p.m., when Sunshine Foods closed early. The Blue Flower closed at 11:00

p.m. every night, which meant that, on an ordinary day, reaching the workers’

dorm grimy and tired at around 9:30, then leaving to wait in line for my more

senior dorm mates to finish showering, then to scrub off the residues of a

thirteen-hour workday, then to change clothes and make myself presentable, then

to walk the twenty minutes or so to the Blue Flower…it simply was not possible.

On Sunday, though, there was plenty of time.

My body might have ached from head

to foot, but the inspiration of love readily overpowers such trifles. I would

wash up at the dorm, having skipped lunch, so that I could better savour the

meal at the Blue Flower later, which would be expensive already for a Chinese

restaurant judged by Sint Maarten standards, and a positive luxury on my

below-local-minimum-wage income (but an absolute necessity in terms of my

purpose on the Island). I would spend the next several hours hanging out with

Keon, Chamel and Lindo, shooting the breeze (as we say in Canada). Of course,

Xinyi would always be the number one topic on my mind and tongue. Maybe I would

stop by Wu, though I didn’t necessarily want to on days like that, at least not

for too long, because of his pessimism and his spiteful hatred of Xinyi and her

family for reasons that, besides a generally shared opinion that they were

beyond the bounds of reputable society, weren’t very clear…certainly, he’d

never been mistreated by Xinyi or her mom, but that was no obstacle to looking

down on them. Then, once darkness was falling and the dinner hour was night, I

would marshal my courage and walk the route up Illidge Road, left at the

Roundabout, onto Zagersgut Road, past the mint-green-and-white People’s

Supermarket, the big-blue-and-white English Seventh Day Adventist church and

the small yellow Spanish Adventist church, to the Shell gas station, turn right

onto Bush Road…at the same building which houses the Jerk Hut, which yet

stands, to its left as viewed from the street…and into the Blue Flower.

Ahhh! Even now, as I sit and write

in my apartment in the Country Club atop Long Mountain, overlooking Kingston

and the Caribbean Sea, just past sunrise on this rainy May morning, when I

retrace my route…even though the Google Map of Philipsburg has no “street view”

available and I’m only using the grey minimalist roadmap, I get a hint of that

overwhelming, gooey feeling, slightly lightheaded, my legs feeling every so much

like they’ve turned to jelly! I have no idea if Xinyi, whatever she’s doing

now, misses me or if the same memories and feelings ever intrude upon her

waking or sleeping mind. I hope that they do, more than I hope for anything

else. Aye, as I prepare to set down my fountain pen and type this up, I realize

all the more that, whatever I might achieve, if achieve I do, in my legal or

other career here in Jamaica – or any other part of the world – it must pale

into insignificance next to the smile in those furtive, deep-set eyes of

obsidian intensity that I saw in a Chinese restaurant on Bush Road,

Philipsburg, Sint Maarten. Also, I know that the “love” (which term people use

so lazily) that might be inspired by a Canadian passport, professional salary

and a bag full of degrees is like an insult next to that which a little chef

and catherdess felt for a broke, artsy, foolhardly illegal immigrant coolie

working in a supermarket down the road. 小猫,我想你!